Viewers who watched Breaking Bad loved the thrill of being along for the ride of its’ protagonist’s transformation from a mild-mannered chemistry teacher to a drug kingpin. Fans rooted for Walter White as he committed increasingly evil acts as they curiously awaited the peak of his empire and its’ inevitable end. There was a certain allure to watching Walt let go of his fears and realizing his full, monstrous potential.

Better Call Saul, a prequel, focuses on the sleazy, ‘criminal’ criminal lawyer and comic relief, ‘Saul Goodman, introduced in Season 2 and a popular character till the end, where he disappears under the alias ‘Gene Takovic,’ a Cinnabon store manager in Omaha, to avoid being arrested.

Unlike the thrill of Walt’s transformation, much of Saul’s fate is already known when Better Call Saul begins. The show gets his post Breaking Bad fate out of the way in the first scene.

The show is set in 2002, 6 years before Saul’s appearance in Breaking Bad, showing us an empathetic, caring, and charming Jimmy McGill, which begs the question – how did this person become the Saul who casually suggested that Walt kill his close friend and brother-in-law?

Granted that there is a lot of room for comedy, given that Jimmy/Saul’s character has a great sense of humor, and Jimmy is constantly up to some ‘chicanery.’ However, there is no addictive thrill here because you see an earnest, hardworking Jimmy. The show works backward; instead of showing you how a person goes from being a teacher to a meth kingpin, this shows the trajectory of someone whose doomed fate you already know. It’s a fatalistic tragedy of moral decay.

How do you make a tragedy like that not only watchable but entertaining and even addictive?

The premise does not look like an easy watch.

The show does this by:

a) Introducing new, likable, and interesting characters who don’t exist in Breaking Bad, which makes you wonder, what happens to them by the end of Better Call Saul?

b) Bringing in characters from Breaking Bad, whose backgrounds and connected paths with Saul viewers always wanted to understand. The shows feel more like a Saul-Mike-Hector-Gus prequel than a standalone Saul Goodman one.

c) Introducing two characters to tie up all the loose ends between the pilot of Better Call Saul and the homonymous episode of Breaking Bad

d) Lastly, and most importantly, by perfecting the ‘show, don’t tell‘ approach of storytelling. Instead of using the technique to immerse the viewer into the story and avoid exposition, the show masterfully uses this technique to add mystery and tension in a way no other show can, despite showing you precisely what the characters are doing.

Breaking Bad gave away little about Saul’s origins but revealed that Saul Goodman was not his real name and that his real last name was McGill. He tells Walter during their first meeting, “The Jew thing I just do for the homeboys. They all want a pipe-hitting member of the tribe, so to speak.”. Bob Odenkirk noted in an interview that his Breaking Bad caricature is often shown only as a lawyer, in ‘work mode.’

This gave the creators a lot of freedom on working with these characters. The same applies for Mike, Hector, and Gus Fring.

Comedy

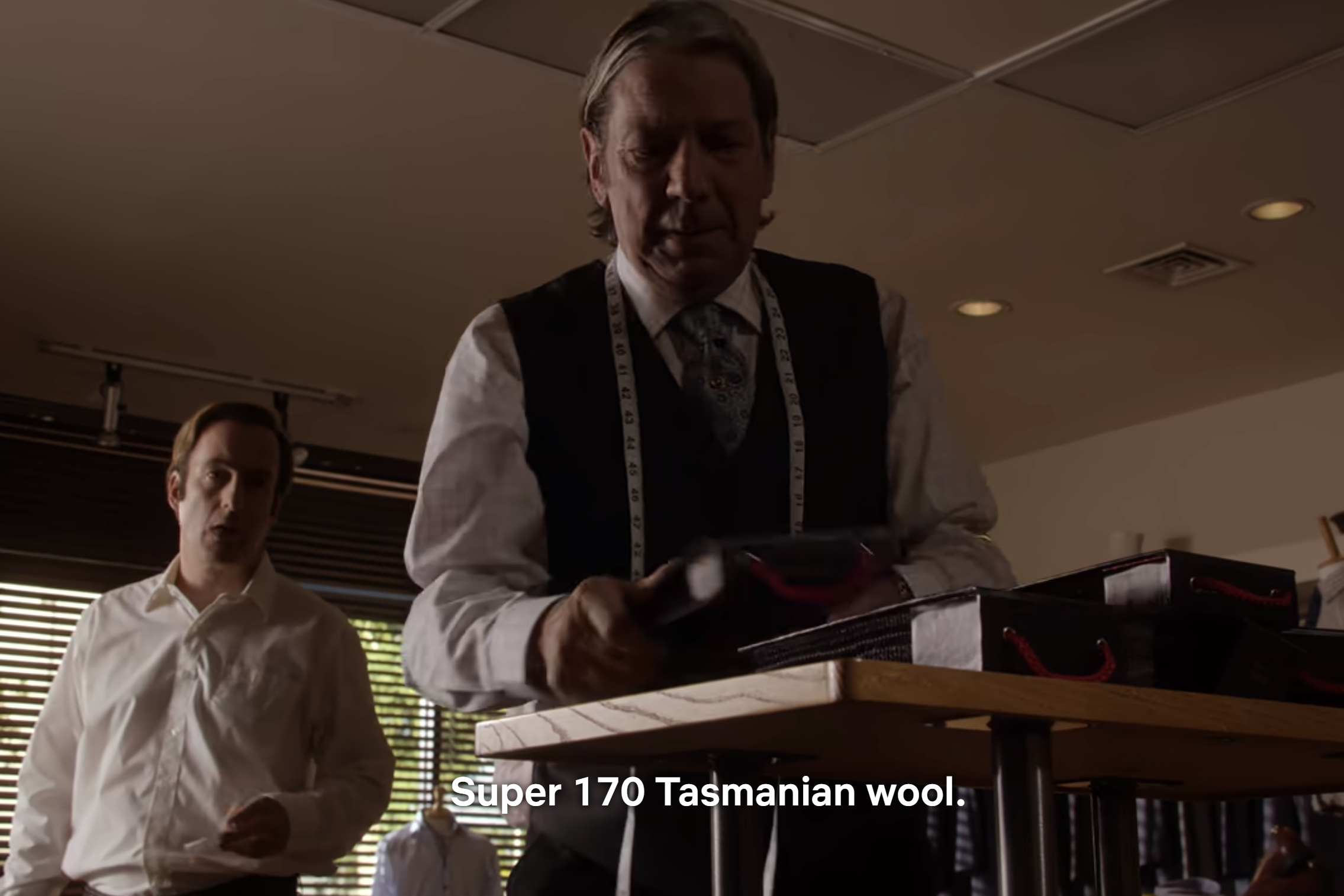

The first unique use of Show, Don’t Tell we see is in S01E04, where Jimmy has come into a bunch of money, and you see him at a high-end tailor. The requests, although specific, seem to be in good taste at first, just giving the impression that he’s treating himself with the finer things in life.

However, as the requests get told from a piece of paper, and increasingly specific, ‘Pinstripe Blue suit’, ‘Super 170 Tasmanian wool’, ‘sea island cotton, and a white club collar and French cuffs’, you start to suspect that some classic Slippin’ Jimmy shenanigans are at play.

By the time we get to Jimmy changing his hair at the nail salon parlor, we’re starting to catch on.

When you get the final product, which is Jimmy making a billboard advertisement dressed exactly like Howard Hamlin, his nemesis, you can’t help but laugh. The whole 6 minute setup above works like a long joke, with the final shot below its punchline.

A lot of fun in the show comes not from wondering what the characters are going to do, like in most television, but rather why they are doing what they’re doing – and sometimes, when we know the why, figuring out how the action is going to lead to their desired outcome.

The show plays a lot with the concept of moderate incongruity – letting you reconcile seemingly unrelated actions with plot points mentioned earlier that seem only mildly related. In the case above, Jimmy was peeved that he was asked not to use his own last name ‘McGill’ at his law practice as he shared the name with his older, more successful brother, who was a partner of Howard Hamlin at Hamlin Hamlin McGill. This does not seem to reconcile directly with the 6 minutes of actions that follow till you realize that the whole ploy was intentionally used to downplay his use of the McGill name. Solving the puzzle before the show gets to it is half the fun.

Empathy

Most of the characters in the Breaking Bad/Better Call Saul universe, including Saul and Mike, are morally ambiguous at best. However, they do have a lot of redeeming qualities, especially in the years before Breaking Bad.

In a later season, Chuck says about Jimmy, “My brother is not a bad person. He has a good heart. It’s just…he can’t help himself.”.

However, by this time, we don’t need Chuck to tell us this to know this about Jimmy because we’ve seen this for ourselves.

The show doesn’t tell us to care about Jimmy or sympathize with Mike. It shows us them struggling in their daily lives and trying their best to stick to their principles in difficult circumstances.

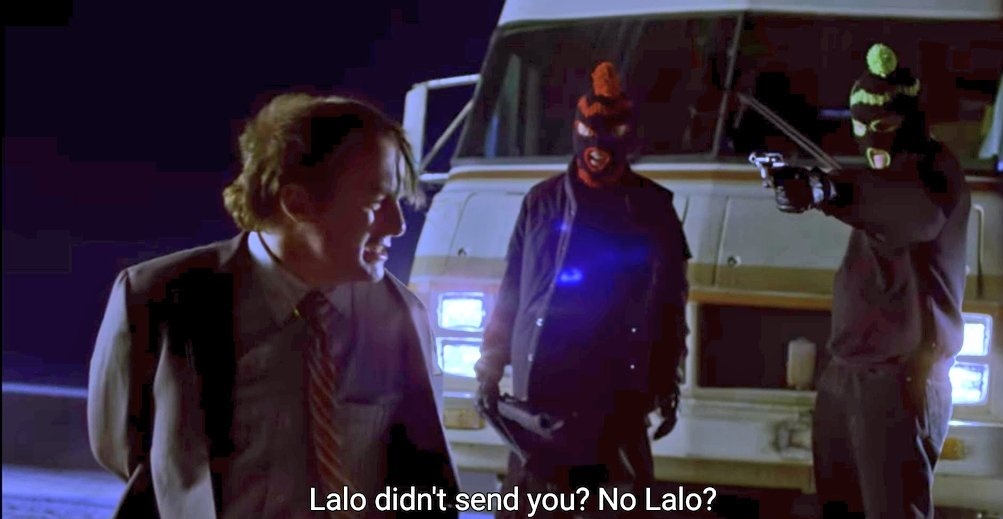

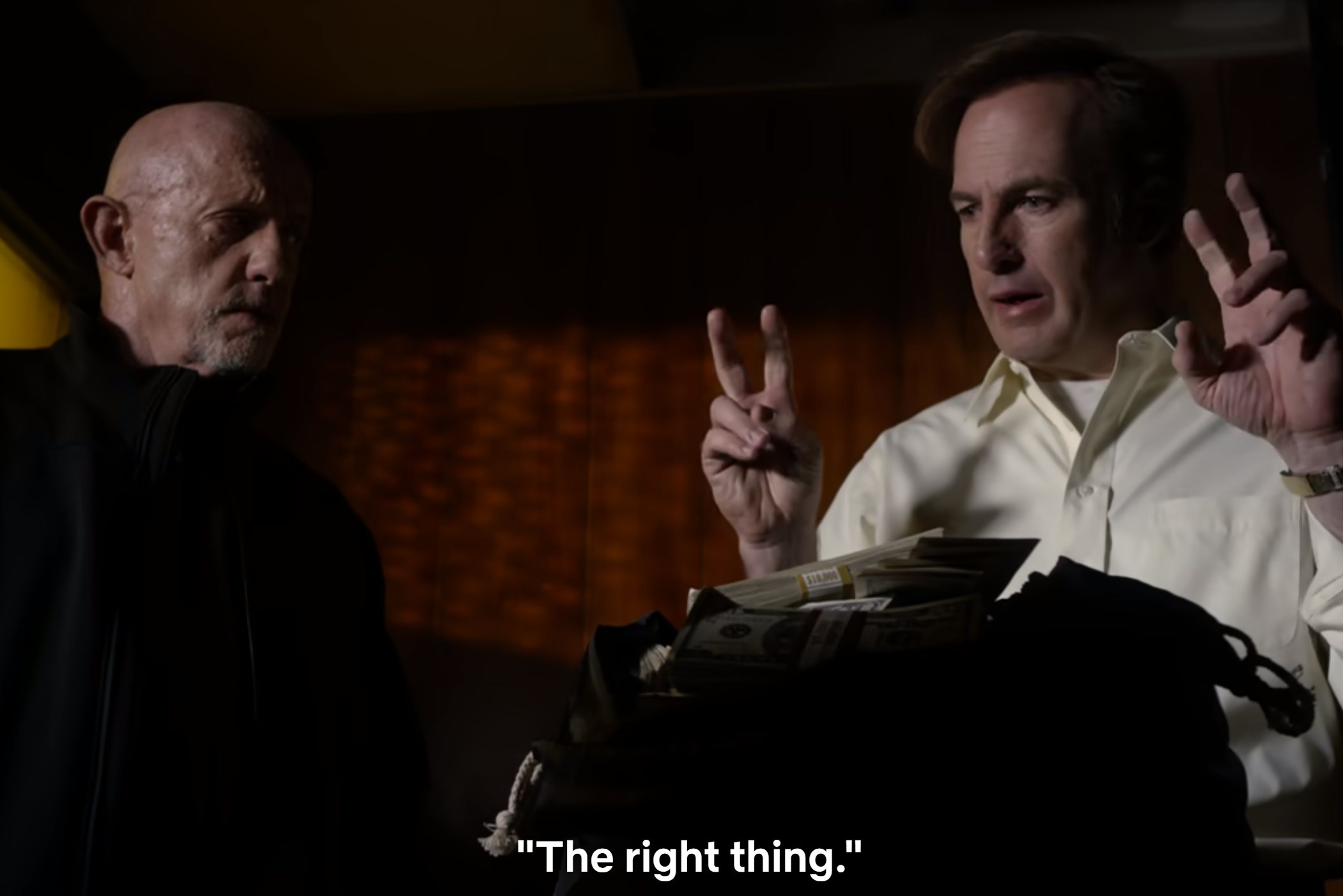

In Season 1, we see Jimmy and Mike deliver the 1.6 million dollars to a district attorney that Mike helped him ‘steal’ from the Kettlemans to get them to accept a guilty plea. Jimmy does it to help his friend Kim and to do ‘the right thing.’ When he asks Mike why he didn’t run away with the money, Mike says, “I was hired to do a job. I did it.”

Here’s a ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ shot – Mike, usually stoic but firm about the rules at his parking attendant job, waves off a car without checking their fees because he’s on the phone and getting a chance to babysit his granddaughter.

Consider the below. We know that Jimmy’s brother, Chuck has a mental condition where he feels that he is allergic to electromagnetic fields and thus can’t bear any electronics nearby. Everyone leaves their electronics outside when going inside his house. Although this is something Chuck can notice, Chuck can’t know whether everyone has ‘grounded’ themselves by touching the metal rod outside his home before they come in. We are shown that Jimmy does this every time. It is respectable that Jimmy does it when they are on good terms, but you truly understand how much Jimmy respects and cares for his brother’s wishes when you see him doing it every time afterward when they don’t see eye to eye as well. These are subtle one-second shots that say so much about Jimmy.

Reduced exposition

The show goes out of its way to avoid unnecessary exposition, when the point is to add dramatic effect and the viewer can anyway reasonably guess what is being said. In the scene below, we know exactly what happened – without hearing a word – that HHM chose not to hire Jimmy – based on context and body language.

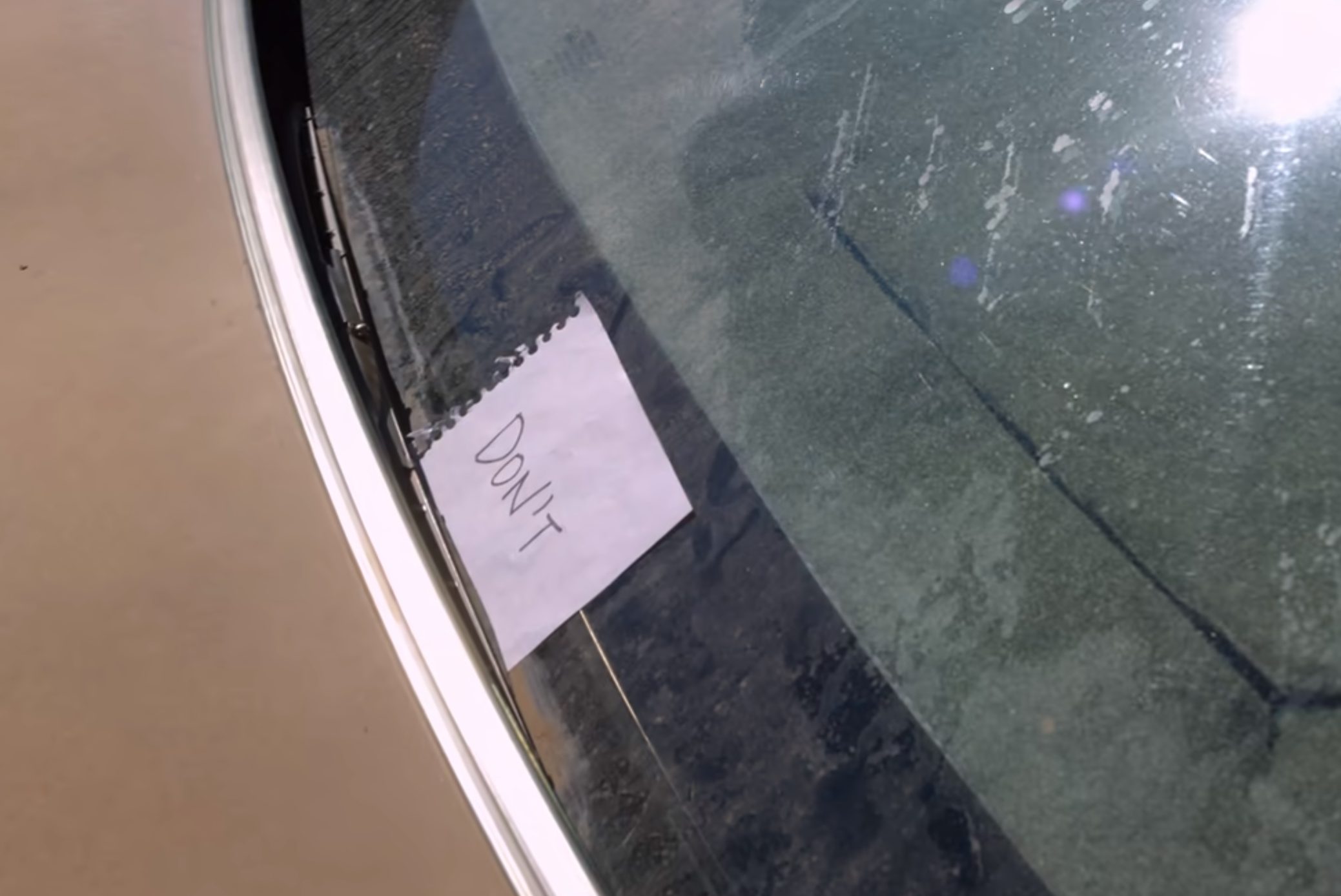

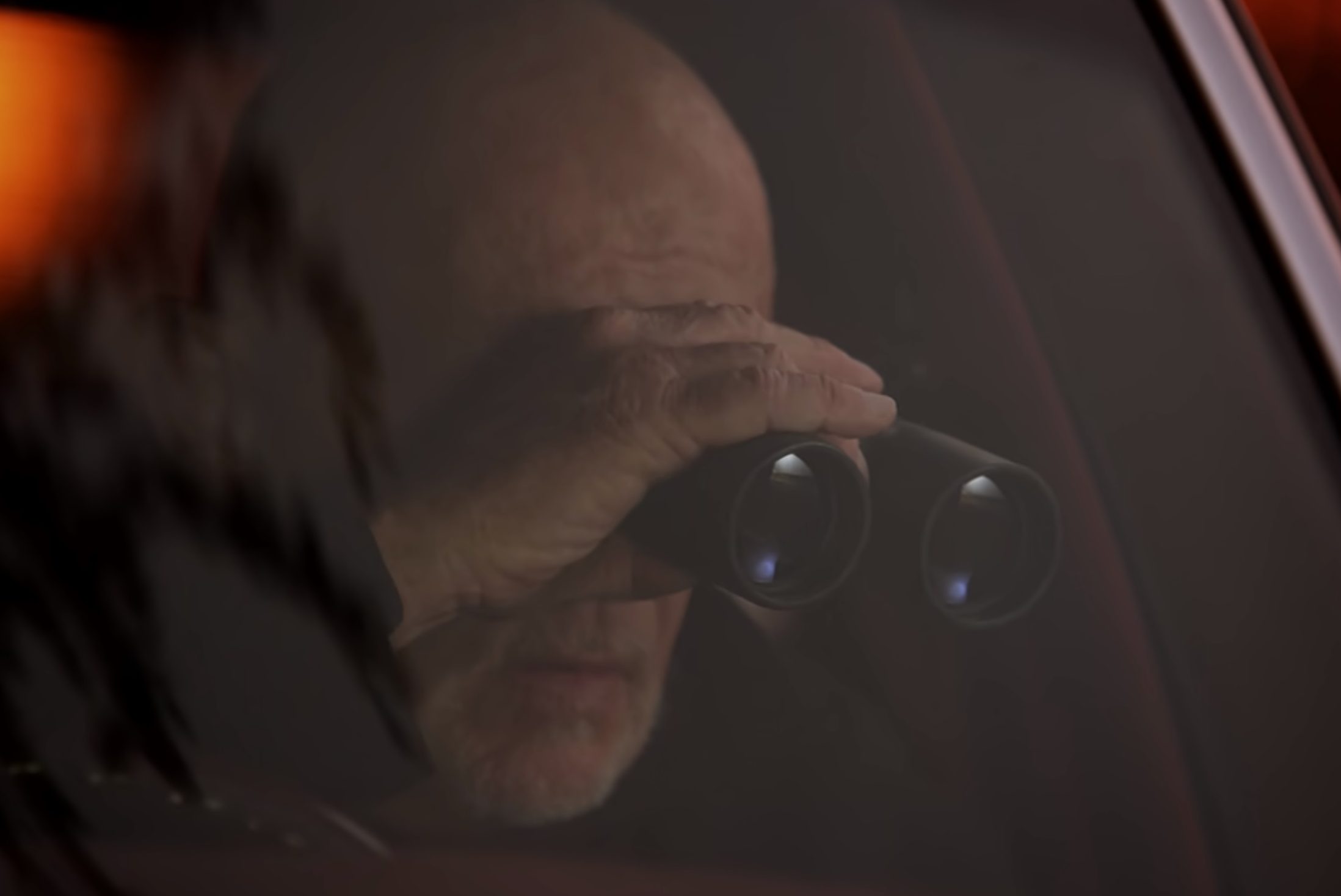

Organic Mystery

This approach also works well in building organic mystery and intensity and slowly dialing it up as we get to the final resolution or big reveal. Toward the end of Season 2, as Mike’s plan to shoot Hector in the desert with a long-range sniper nears its’ end, his car starts blaring, forcing him to abandon his plan and shut off the horn. He is left with a note, saying ‘DON’T.’ This arc continues in early Season 3, where for the most of the first episode, we deal with Mike’s paranoia and meticulous search for a tracker, as it is the only way someone could have known he was out there, and his attempt to use a similar one to find this mysterious person. The scenes span three episodes, about 40 minutes of screen time, and yet have no dialogue from Mike. This is a signature example of many Mike scenes, as they respect the audience’s intelligence and ability to interpret what’s going on.

If you think the above is painstakingly detailed, it is. Many lesser shows would have settled with lazy writing and a character saying something along the lines of ‘I found a tracker and switched them to track the person who was tracking me.’ However, the way Better Call Saul deals with it also serves another purpose – of appreciation. Appreciation for

a) the meticulous, methodical nature of Mike

b) the resourcefulness, planning and patience, and lack of error that goes into what Mike does to stop being followed, but instead follow the person back without suspicion

c) the writers’ research into the smallest details and effort into making the final ‘aha!’ reveal feel earned for audiences.

The show is a masterclass in telling a story well when you already know the end, and in using patient, slow scenes to keep you addicted. It doesn’t try to grab your attention; it demands it.

But if you give it your attention, it will reward you.